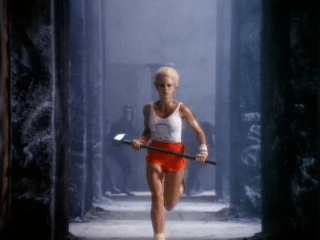

Forty years ago, Apple changed the world when they launched the Macintosh computer, with a superbowl ad echoing Orwell’s 1984. So the story goes anyway. Reading that (really very good!) piece from Siva Vaidhyanathan in the Guardian this morning, I was struck as I so often am by the declaratory confidence of the headline. WORLD CHANGED; MACHINE LAUNCHED. Vaidhyanathan layers it on, claiming that the launch could be seen as ‘the beginning of the long 21st century’. It struck me in reading that we are now starting to see the end of the twentieth century as a historical phenomenon, and writing about it in a way that seeks consistency and consensus, in the same way as there is consensus about the rest of history as we have learned it – that there were two world wars in the 20th century, that the Cold War was between America and Russia, that the EU was formally launched in 1993, and so on. In structuring history, we superimpose salience upon people, and events, that may not have been obvious at the time, and that possibly misshapes our understanding of the world we live in today.

Now, on both a micro and macro temporal level, this attribution of salience to the launch of the Macintosh in 1984 is clearly technically wrong. At a micro-temporal level, to claim the launch as a special moment ignores the contingency of invention, planning, design, prior failures, deaths, shower-ideas, and countless other elements that contributed to the launch, all of which will have happened in the years prior to the launch. In a similar way, had the launch not been followed by effective sales execution, complex Microsoft – IBM – Apple politics, the absence or sluggishness of genuine category competitors, and all the rest of it, we would not now regard the moment of the launch as having been important. Each of these things happened in the years after the launch. On a macro-temporal level, our concepts of time are arbitrary to begin with, and whether the 21st century began then (January 1984) or with the fall of the Berlin Wall or with 9/11 – lots of different folks will offer a view; and that’s merely in the west. Perhaps it began in 1989 with the Tiananmen Square Massacre, or the Argentinian recession of 1998, or the Russian ruble crisis of 1998.

We often speak in similar terms about people. Steve Jobs changed the world, or Ronald Regan changed the world, or tank man changed the world. Each of them has contingency and process. Steve Jobs died in 2011, when Apple stock was worth about $14. Today, it’s worth more than ten times that – but we don’t say that Tim Cook is better than Steve Jobs. If Ronald Reagan had died when he was shot in 1981, does anyone think that George H W Bush would not have pursued a similar foreign policy? Was there something unique about Ronald Reagan that made him less ordinary? Jobs and Reagan may have been charismatic – and that’s not unimportant – but to attribute to them some kind of elevated personal status as historically significant figures appears more a contribution to narrative structure (also not unimportant), rather than a genuine representation of any kind of truth.

Of course, there isn’t one history. There’s my history, and there’s a history that I share with my community – whether that’s locally, in Ireland, in Europe, or in the West. That’s what we call history, essentially a shared narrative – sometimes contested – that is broadly agreed upon. The contestation can be localized – there are usually two sides to the history of conflict, whether that’s in the North of Ireland (also referred to as Northern Ireland by those of a Unionist persuasion) or in the southernmost of the United States in considering their civil war / war of northern aggression. Few in Africa regard such narratives as central to their experience, save insofar as it informs their insights into human behaviour, much as for example we might consider the Peloponnesian War, recorded, it should be added, by a single historian. Even my history, though, if I reflect upon it, is flawed. I misremember things, and other things that I should remember, I simply forget. In language at least (and the image as history is a whole other thing) history is little more than a fiction, but one that we elevate as sacred in some sense, not unlike the bible.

I’m reading Gaddis’ The Landscape of History; The Philosophy of History: Talks Given at the Institute of Historical Research, London, 2000-2006 edited by Alexander Macfie; and Bruno Rossi’s Moment’s in the Life of a Scientist. Also listening to David Roochnik’s excellent audio course on Plato’s Republic. Strong recommend.

I’ve not been posting as much here on SL as usual – I have had a pretty consistent cadence of one post per month for over ten years now, but in the past six months I’ve been pretty committed to a book, of sorts, that has been gestating for some time. It’s a book about history, and physics, and coincidences of time and space, things that happened in the same place but at different times, and things that happened at the same time, but in different places. Within that simple construct, we ask ourselves what exactly does it mean to be in the same place but at different times? To paraphrase Heraclitus, no man ever stepped in the same river twice, because it was a new river, and he was a different man. So the same geo coordinates may apply, insofar as we can find some consistency in that system, but are they really the same place? The same question applied to temporal coincidence is even more vexing, and brings us to the questions of quantum mechanics and relativity theory. Doubtless it will remain on my hard drive or some cloud share, but the process has been edifying and fun. Perhaps when it is rejected by publishers – should I ever finish it – I may post it here!!