Can we believe in AI? What does it mean to believe in AI? Is there truth in AI? Can AGI be in any sense profound, or revelatory? In many respects, AGI represents an imminent (immanent?) apotheosis in the modern liberal project: a realization of the bureaucratic, scientific model of the modern world, in automated magnificence. It heralds the potential for what Aaron Bastani calls – perhaps tongue-in-cheek – fully automated luxury communism. It appears on our horizon as a new end of history, our new Berlin Wall moment, our New Jerusalem. The State as a politico-philosophical project has intellectually been a quest for individual freedom; the most freedom, for the most people, avoiding the Hobbesian dystopia of all against all. Could AGI allow humankind to transcend the state as the fundamental organizing structure?

Continue reading “The Poverty of AI”Category: AI

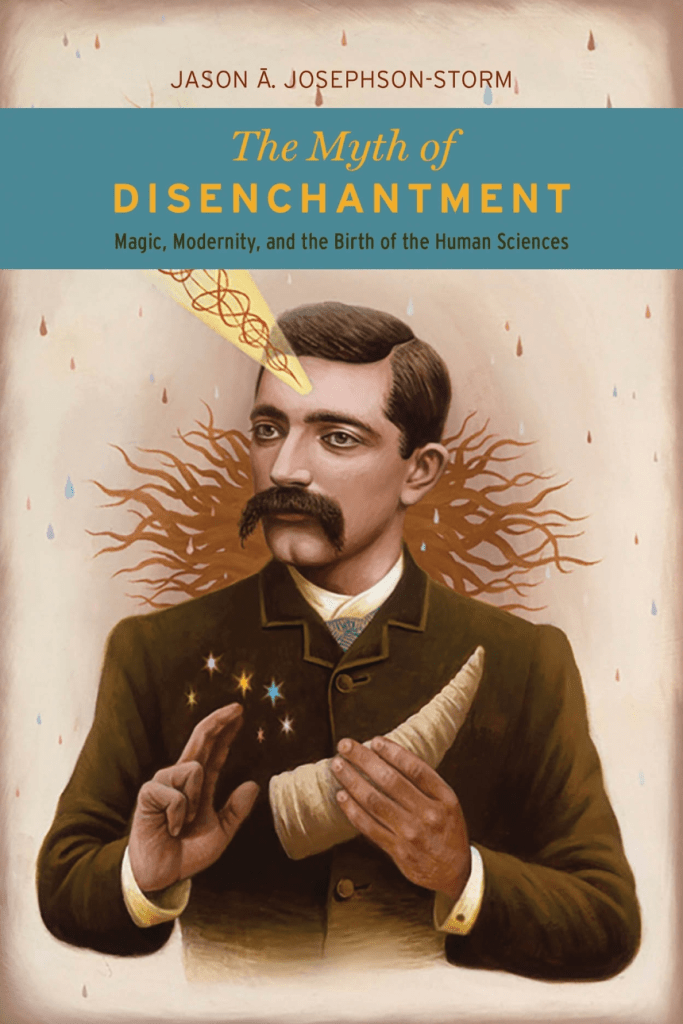

There are two major projects that I am driving – the book(s) project, and an ongoing investigation into the epistemic challenge of technology, if indeed such a challenge is manifest. The books (there are three), without giving too much away, revolve around the development of early twentieth century cultural theory and its intersection with science, in tandem with early Reformation cultural transformations and historical narratives. The tension between science and religion, and within systems of belief are central to both projects. In the work on technology, the concern that I have been exploring for almost ten years now, if not more, is whether AI can supplant our history and our science as a source of some kind of institution of truth. Each project explores how we know what we know, how it informs our social and political structures, and how epistemology develops – a kind of techno-episteme.

Continue reading “Magic, Religion, Science, Technology”

The Berinmo people of Papua New Guinea are a small tribe of people with a curious flourish in their language. Specifically, they do not distinguish between green and blue, and they have two separate words for types of yellow. This has deep implications for those who argue for a consistent and objective real (universalists), and the ultimate possibility of artificial intelligence. We’ll come back to the Berinmo, and color linguistics later. While strategies for the avoidance of bias in AI focus on the injury of minority oppression and design failings in creator preference, a deeper semantic analysis of some of the fundamentals of AI reveal several foundational assumptions that give cause for concern. Simply put, the fundamental task of an AI is to construct an image of the world within the parameters of its design (from narrowly defined chatbot engines to Artificial General Intelligence or AGI), which in turn establishes the context for automatic machine decisions to be made. In order to arrive at that image of the world – the simulated real – there are several intermediate layers that each introduces a risk of misinterpretation. This article will walk through each, and understand where some of those challenges might lie. But first, Heidegger.

Continue reading “The Ontological Layers of AI”

One of those things that I do during the end of year break is to tidy things up. Tidy up the garage, the office, and the various computers and storage devices in the house. Digital historical artefacts have become a thing now – photos and home movies especially – and making sure that they are backed up, either on physical hardware or in a reliable cloud somewhere is not straightforward. It led me to consider why we collect these things.

Continue reading “On memory, forgetting and time.”

Extending from the last missive on Computational Theology, I want to dive into the question of what it means to have a theology of machines, a machine theology, or a theology generating machine. Each of those three descriptions is different – a theology of machines is about believing in machines as otherworldly things. It’s a little challenging to think about how we might worship a toaster, but perhaps less fantastic to think about how we might worship a machine that no one had ever seen before, and that landed on earth from outer space. A machine theology asks what do machines believe? To assign belief to a machine, to assert that machines demonstrate a teleological sensibility, may be a stretch; but let’s see, shall we? When we consider ‘machine ethics’, we are opening up Langdon Winner’s question of whether artifacts can have politics; I go further than he does. Winner suggests that a machine can’t have its own politics, but that it can embody political biases. I would argue – in considering the distinction between lived and transcendent theologies that I wrote about in my last post, and the further distinction of strong lived theologies that trend towards the transcendent – that advanced machines machines can possess a strong lived theology. A theology generating machine is a more future looking device that predicts likely futures based on a Laplace’s Demon kind of model, becoming through its predictions a time machine of sorts. It has parallels in the Oracle at Delphi, Psychohistory in Asimov’s Foundation series, and is grounded in the biblical divinity of prophesy (the prophets, those who tell the future, are closer to God), and ancient practices of divination.

Continue reading “Theology and Technology in Review”

In considering my proposal of technological theology as a waypoint in our current trajectory, from religious, political and economic theology, the idea of epistemic theology was brought to my attention in considering the grounding of Carl Schmitt. There have been questions about the theology of Schmitt (was he primarily Christian, or secular?), and some questions over whether political theology is about the politics of theology or the theology of politics; medieval political theology certainly appears to have been about the latter. Adam Kotsko suggests political theology is more concerned with the relationship between the two fields of theology and politics, though the consensus is moving towards what he calls a politically-engaged theology. My reading, reflects a range of kinds of theology, in that political theology is an ontological structure, allowing the world to be understood and engaged with. Just as Deleuze and Guattari argued that the role of the philosopher is to ‘create concepts’ (What is Philosophy?, 1991(FR), 1994(transl.), Columbia, p.5), so political theology is a way to understand the world, to understand the real in social, or more specifically political terms. It is, in Schmitt’s explanation, a secular theology (Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty, Chicago UP, 1985/2005).

Continue reading “Epistemic Theology and Epistemic Technology”In the late nineteenth century, as the Industrial Revolution kicked into gear, social alienation became a significant concern of both social workers (in particular religious pastors and ministers) and policy makers. Durkheim’s anomie was one of the first studies of the phenomenon (The Division of Labour in Society, 1893), though it’s conceivable that such alienation was only made possible by urbanisation and the size of communities permitted through industrialization. Simmel (The Philosophy of Money, 1900) and Tönnies (Community and Civil Society, 1887) each looked at the money system and the built environment respectively as contexts for understanding alienation. Man was alienated from his species essence, in Marxist terms, a fundamentally economic alienation from labour and the product of that labour. The fullest expression of that alienation is ‘in the role of machines in modern life,’ (Wendling, Karl Marx on Technology and Alienation, 2009) those things that take touch away, that dehumanise. The industrialisation of the machine in the form of the city scaled that effect to community and social dimensions.

Continue reading “Loneliness and The Cyborg Transmutation”

In Martin Heidegger‘s Being and Time, he refers to verfallen as a characteristic of being, or dasein. It means fallen-ness, or falling prey, an acknowledgement that we do things not because we want to do them, but because we must; we act in particular ways, we fall into line, we do jobs, have families, get a mortgage and a pension, obey the law and so on. We consciously engage with the systems and societies into which we have found ourselves. It is surprising how frequently this concept of ‘the fall’ emerges in philosophy, theology and popular culture.

Continue reading “Falling Down”

AI poses several challenges for the religions of the world, from theological interpretations of intelligence, to ‘natural’ order, and moral authority. Southern Baptists released a set of principles last week, after an extended period of research, which appear generally sensible – AI is a gift, it reflects our own morality, must be designed carefully, and so forth. Privacy is important; work is too (we shouldn’t become idlers); and (predictably) robot sex is verboten. Surprisingly perhaps, lethal force in war is ok, so long as it is subject to review, and human agents are responsible for what the machines do: who those agents specifically are is a more thorny issue that’s side-stepped.

Continue reading “World Religions and AI”