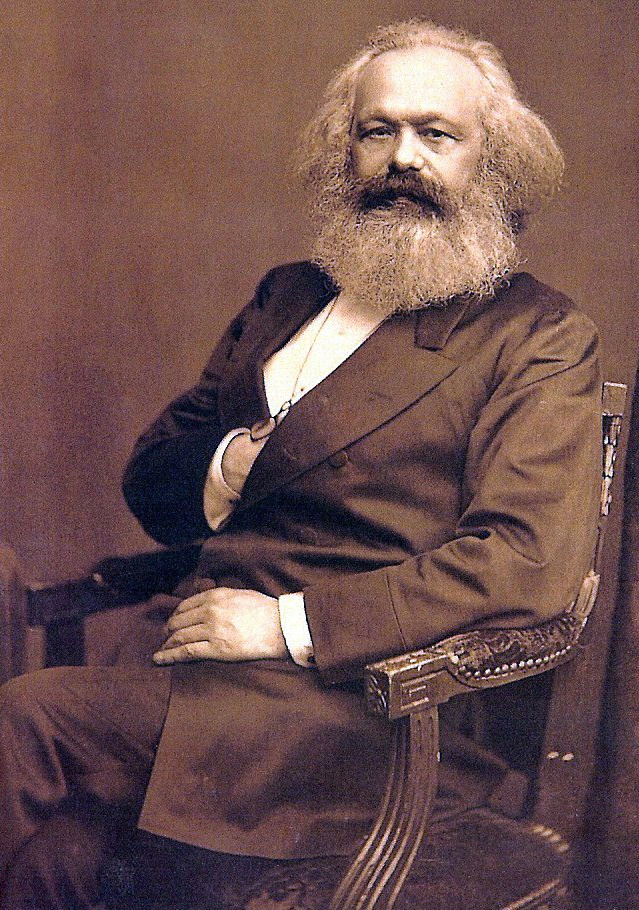

Property, and – as philosophers might refer to it – the claim to possession and ownership of externalities, has long been a source of some disquiet. Jean Jacques Rousseau in the Second Discourse (The Discourse on Inequality) begins the second part with the dramatic opening line ‘[t]he first man who, having enclosed a piece of ground, bethought himself of saying This is mine, and found people simple enough to believe him, was the real founder of civil society.’ Plato before him and Marx later both advocated collectivisation, but Rousseau was no communist. The reality of what man had become made such reconstruction impractical. Yet the concept of property has led to inequalities that threaten capitalist society. Slavoj Zizek suggested that ‘…today’s global capitalism [may] contain antagonisms which are sufficiently strong to prevent its indefinite reproduction…’ including what he called ‘…the inappropriateness of private property…‘ especially intellectual property. Rousseau’s prescription was The Social Contract, and the abstraction of the General Will, an investiture of political legitimacy in the sovereign.

The Social Contract is not perfect, of course. While the abstract philosophical structure represents a social order that manages compromises, individual freedom is not well protected at the margins, especially for minorities, and arguably the construct itself has a deterministic character. Society embodied in an overbearing political structure can ‘suggest’ a propriety of the group that denies individualism, and blunts the edges of art. Rousseau’s concept of the amour propre, a kind of dangerous narcissism borne of man’s association with and reference to other men, takes the fundamental concept of property and converts it to a personal value judgement, an extension of the ego, of identity. Rousseau believes that ‘self-love’ is not a sufficient representation of self-interest: that is merely the survival instinct, the instinct for compassion. The amour propre is something more akin to Hobbesian vainglory, to Platonic Thumos, something socialised, referential, and caused by man beyond the state of nature. Where perhaps self-love may have been an evolutionary or biological necessity, the amour propre is the result of when man ‘…began to look at the others and to want to be looked at himself and public esteem had a value.’ It was something learned, socialised, evolved. It was designed externally, and internalised; it was not part of ‘naked’ man. Self-love tells me I need a roof in order to shelter and protect myself, and my family. Amour propre tells me I need a Porsche.

Continue reading “The Political Philosophy of The Blockchain”