In the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008/9, many commentators argued that the old neoliberal consensus had finally been dealt a hammer blow. If 9/11 had been a wakeup call for the West to recognize the weaknesses in the global system, due to its inherent inequality and the problems of globalization, now the impact of neoliberal disequilibrium would be felt at home, and domestic politics would be forced to drive change. People and leaders suffered – bankers were fired, governments replaced, and companies destroyed – but new people and companies replaced them, and appeared to resume the old model. For the past ten years or so, it’s been difficult to figure out what’s been going on. We know it’s a failed model – so why do we persist with it?

Continue reading “There Is No Market For Happiness”Category: Markets

In considering my proposal of technological theology as a waypoint in our current trajectory, from religious, political and economic theology, the idea of epistemic theology was brought to my attention in considering the grounding of Carl Schmitt. There have been questions about the theology of Schmitt (was he primarily Christian, or secular?), and some questions over whether political theology is about the politics of theology or the theology of politics; medieval political theology certainly appears to have been about the latter. Adam Kotsko suggests political theology is more concerned with the relationship between the two fields of theology and politics, though the consensus is moving towards what he calls a politically-engaged theology. My reading, reflects a range of kinds of theology, in that political theology is an ontological structure, allowing the world to be understood and engaged with. Just as Deleuze and Guattari argued that the role of the philosopher is to ‘create concepts’ (What is Philosophy?, 1991(FR), 1994(transl.), Columbia, p.5), so political theology is a way to understand the world, to understand the real in social, or more specifically political terms. It is, in Schmitt’s explanation, a secular theology (Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty, Chicago UP, 1985/2005).

Continue reading “Epistemic Theology and Epistemic Technology”

In a very crude sense, the western history of political philosophy can be divided into five phases: the city state Greek democracy, an oikonomia derived in Ancient Greece from a principle of agreed control; colonial empire, deriving first from the Greek colonies and extending into the military-bureaucratic structures of the Roman empire; federalist patrimonial states, an essentially feudalist structure allowing for larger domains to be managed through grace and favour; and modern variations on social democracy (including communism) since the French Revolution, based on concepts of individual equality and freedom. Max Weber, Francis Fukuyama and countless others have variations on these phases and structures, some more global (Fukuyama in particular considers Indo-Sino histories), and others more scientific (Weber’s forensic sociology in particular).

Continue reading “Failures of Political Philosophy”

On the day when Apple are supposed to be launching a new iPhone with facial scanning capability, the Guardian has delightfully timed a piece warning of the dangers of the technology. Its functions potentially extend to predicting sexual orientation, political disposition, or nefarious intent. What secrets can remain in the face of this extraordinary power! Indeed, it’s two years ago since I heard Martin Geddes talking about people continuing to wear face masks in Hong Kong not because of the smog, but to avoid facial scanning technologies deployed by an overbearing security apparatus. There’s no hiding from the data, no forgetting.

Continue reading “Galadriel’s Inversion”

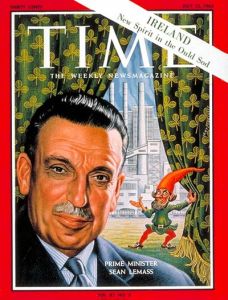

The international system is a complex and convoluted thing, and sets the framework against which States are measured for their effectiveness, righteousness, or other measures that could serve as proxies for legitimacy: transparency, robustness, even happiness, or goodness. According to these indices, Ireland performs reasonably well – very well actually. It is the seventh most ‘unfragile’ country in the world; the eleventh most ‘good’; the 18th most transparent; and the 19th happiest. Most of these indices combine different metrics such as GDP, social metrics like unemployment, education rates, and so on, which tend to mean that Ireland – and other countries – won’t deviate too much from one ranking to the next. So Ireland performs well as a country. However, the combination of the EU Crisis, Brexit, and Trump’s America seem to represent a trifecta of bad things over which Ireland has little or no control, and could send the country hurtling down those indices. So if Ireland has so little control over these shaping factors, is Ireland in fact a legitimate country, a genuinely sovereign power?

There has been much written in recent times about post-truth politics, and much associated naval gazing as commentators, analysts and politicians themselves have tried to understand how to deal with all this. Leave campaigners in the UK promised £350m a week for the NHS; Donald Trump still thinks he opposed the war in Iraq; and Vladimir Putin claimed no involvement with the war in Ukraine. Populism, reactionism, anti-intellectualism – call it what you will, it’s certainly got currency.

There has been much written in recent times about post-truth politics, and much associated naval gazing as commentators, analysts and politicians themselves have tried to understand how to deal with all this. Leave campaigners in the UK promised £350m a week for the NHS; Donald Trump still thinks he opposed the war in Iraq; and Vladimir Putin claimed no involvement with the war in Ukraine. Populism, reactionism, anti-intellectualism – call it what you will, it’s certainly got currency.

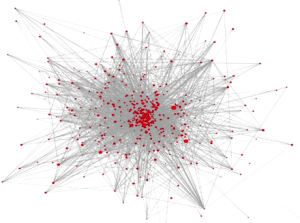

Speaking of currency, the pound has taken a pounding since the Brexit vote, and overnight trading on the 6th-7th October witnessed a flash crash that traders have struggled to explain. David Bloom at HSBC put it that the pound had become the de facto opposition in Britain. ‘Sterling,’ he said, ‘has become a structural and political currency.’ I’d go further than that. It’s the algorithms providing the opposition. The algorithms governing the trading desks even scrape news feeds to see potentially influential stories (one commentator suggested that comments from Francois Hollande on the Brexit negotiations may have triggered the ‘flash crash’). They sense and learn, and respond, constantly scoring and valuing political decisions and the smallest market moves.

The algorithms then form their own truth. This isn’t post-truth politics, it’s absolute truth. And that is potentially a whole lot worse.