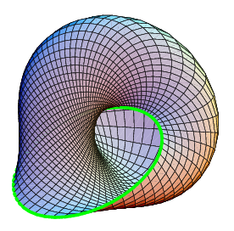

I apologize for not having posted in 2025, but as I had mentioned in late 2024 I was writing a book. The book has been completed, the first one at least, and is off to see if any agent considers it worth hawking around. More on that as we get it. The second book has more to do with science, and how we understand the world, and prompted me to think about a kind of layering of thought, a progression of a sorts, that I have been through myself. It begins – as did this blog – with concerns for politics, and how we manage ourselves – political philosophies. AS one dives deeper into political philosophy, one is drawn into the history of political philosophy, and then the philosophy of history follows soon after. Epistemic concerns lead to the philosophy of science, and how we know what we know, before ultimately we end up back at the philosophy of mind, cogito ergo sum and all that.

Continue reading “Ontological Layering”Category: philosophy of history

As a young man in college – a boy, really – I invited as an officer of the Society of Saints and Scholars at University College Galway (or NUI Galway, as we were being invited to call it) the ‘revisionist historian’ David Irving to come and give a talk on his philosophy of history. To say that he was controversial would be an understatement, although I do remember thinking at the time that the pejorative ‘revisionist’ in the soubriquet to which he was referred seemed both unnecessary and political. Were not all historians in some way revisionist? Otherwise, what was their function? In any case, and I don’t quite remember the ins and outs of the thing, there was a lot of hoo-hah and the event never happened, notwithstanding the man’s acceptance of our invitation.

Continue reading “Historical Revisionism”Forty years ago, Apple changed the world when they launched the Macintosh computer, with a superbowl ad echoing Orwell’s 1984. So the story goes anyway. Reading that (really very good!) piece from Siva Vaidhyanathan in the Guardian this morning, I was struck as I so often am by the declaratory confidence of the headline. WORLD CHANGED; MACHINE LAUNCHED. Vaidhyanathan layers it on, claiming that the launch could be seen as ‘the beginning of the long 21st century’. It struck me in reading that we are now starting to see the end of the twentieth century as a historical phenomenon, and writing about it in a way that seeks consistency and consensus, in the same way as there is consensus about the rest of history as we have learned it – that there were two world wars in the 20th century, that the Cold War was between America and Russia, that the EU was formally launched in 1993, and so on. In structuring history, we superimpose salience upon people, and events, that may not have been obvious at the time, and that possibly misshapes our understanding of the world we live in today.

Continue reading “Cause, Effect, History, Truth”The demise of Liz Truss is as much a cruel personal tragedy as it is the death rattle of the Brexit project, as one columnist said. Times journalist Matthew Parris was even more excoriating, her fate being entirely predictable, as in his words ‘she ha[d] never said anything important or interesting or thoughtful.’ Much had been made of her attempts to channel an inner Margaret Thatcher, a leader still venerated in the Conservative Party for some obscure reason, a woman who had genuinely changed the world – along with Ronald Reagan, of course, similarly worshipped in the American GOP. Yet how much can truly be laid at the feet of these so-called great leaders? And how much should Liz Truss be vilified for her perceived errors and misjudgments?

Continue reading “Contingency & Attribution”One of the key questions in philosophy is whether or not we (each of us) have free will. It is often referred to as the problem of determinism: are our actions pre-determined? Alternatively put: do we in the exercise of our will define our lives, and change the world? The knee-jerk reaction for the post-modern reader of this essay will invariably be ‘yes’! So let’s take two examples of me having exercised free will, determining my own future, one big and one small. I chose to go to college, and as a result I got a good job and had a successful career. And for the small example – I just lifted a pen from the desk. Are these choices entirely made by me?

Continue reading “The Ecology of History: Time, Contingency, and Substance”David Hume’s challenge to the philosophy of science – the problem of induction – has never properly been addressed. In essence, it argues that it is impossible to predict the future, because no matter how many experiments we can do, or examples we can take from history, we can never be sure that something we didn’t know might happen – like the emergence of a black swan, first discovered (or so named) in Australia in 1790, and prior to which – in Europe at least – it was presumed that all mature swans were white. We can deduce that if A = B and B = C then A = C. But just because every car we have ever observed has four wheels it does not mean that the next car will have four wheels. It may have only three. Instead of throwing our arms up and saying that none of modern rationalism can really make sense any more, a combination of pragmatism, wilful ignorance and theology have conspired to sweep the inconvenient position under the carpet.

This has profound consequences for the basis of modern thought and epistemology. In particular, it has particular consequences for history and the philosophy of history, and the philosophy of time. It also has a profound and immediately practical bearing on the criminal justice system, and how we attribute blame.

Continue reading “The Folly of Causation”

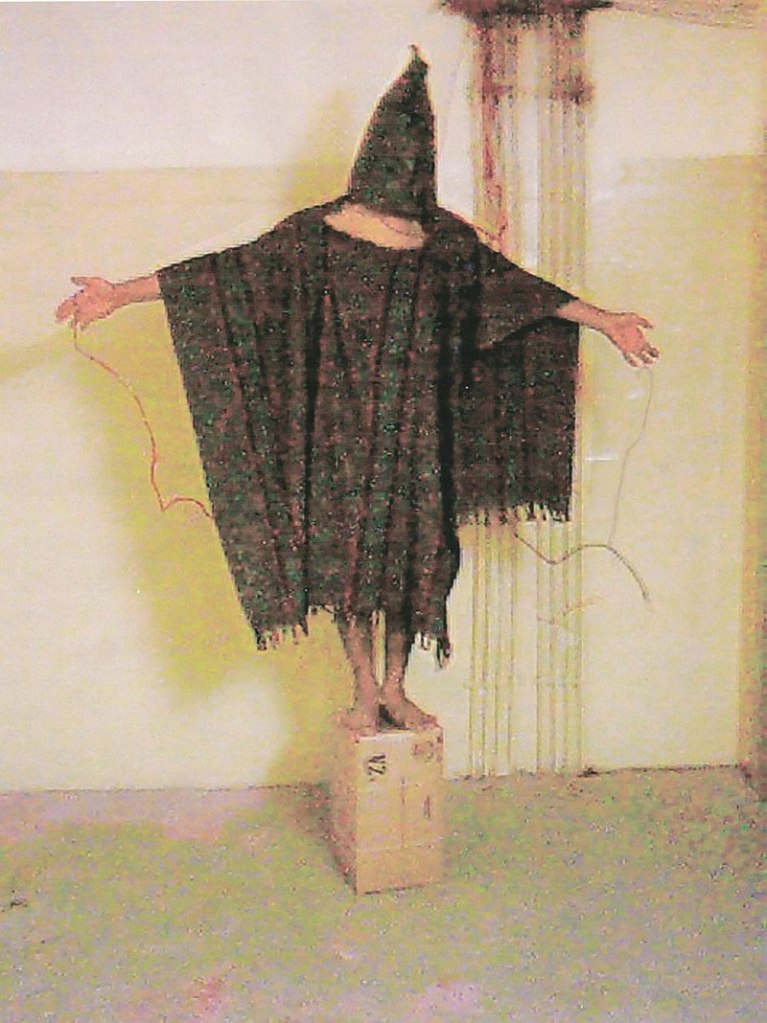

The Chinese appear to have fabricated an image to support a narrative that Australian soldiers committed war crimes in Afghanistan. In the modern media dominated world, negative stories are quickly suppressed and ignored where they can be confidently denied by a robust and well-disciplined communications strategies. However, when there’s a picture, it is more difficult. Audio and video make the story even more difficult, as they lend themselves to blind sharing, hot takes, and indiscriminate proliferation.

In the post-event / post-allegation battle for control of the narrative, and for a definitive version of events, truth becomes defined. The immediate aftermath is the most important time. Witness Bill Barr’s decision to release his (inaccurate) version of the Mueller Report in the US several weeks before the actual report was released; even though it was wrong, and ultimately provably so, the narrative was sufficiently blunted to as to protect his ‘client’, the American president.

Continue reading “The Contested Space of Truth and History”In assessing the battlefield casualties Rome suffered in the first thirty years of the second century BC, Livy (c59 BC – c17 AD) estimates 55,000. The classicist Mary Beard distrusts the figures – and that number, she suggests, is far too low. In the first instance, ‘there was no systematic tally of deaths on an ancient battlefield; and all numbers in ancient texts have to be treated with suspicion, victims of exaggeration, misunderstanding and over the years some terrible miscopying by medieval monks.’ In addition, she continues, ‘[t]here was probably a patriotic tendency to downplay Roman losses; it is not clear whether allies as well as Roman citizens were included; there must have been some battles and skirmishes which do not feature in Livy’s list; and those who subsequently died of their wounds must have been very many indeed (in most circumstances, ancient weapons were much better at wounding than killing outright; death followed later, by infection).’ (SPQR, p.131-2)

Continue reading “The Politics of Posterity”