Can we believe in AI? What does it mean to believe in AI? Is there truth in AI? Can AGI be in any sense profound, or revelatory? In many respects, AGI represents an imminent (immanent?) apotheosis in the modern liberal project: a realization of the bureaucratic, scientific model of the modern world, in automated magnificence. It heralds the potential for what Aaron Bastani calls – perhaps tongue-in-cheek – fully automated luxury communism. It appears on our horizon as a new end of history, our new Berlin Wall moment, our New Jerusalem. The State as a politico-philosophical project has intellectually been a quest for individual freedom; the most freedom, for the most people, avoiding the Hobbesian dystopia of all against all. Could AGI allow humankind to transcend the state as the fundamental organizing structure?

Continue reading “The Poverty of AI”Category: Religion

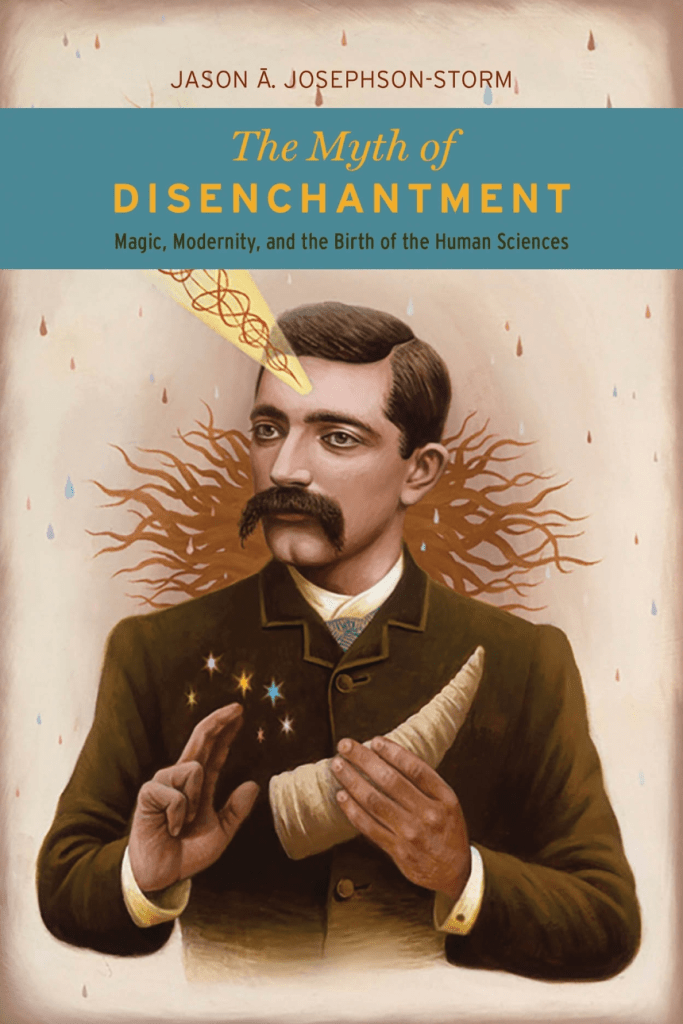

There are two major projects that I am driving – the book(s) project, and an ongoing investigation into the epistemic challenge of technology, if indeed such a challenge is manifest. The books (there are three), without giving too much away, revolve around the development of early twentieth century cultural theory and its intersection with science, in tandem with early Reformation cultural transformations and historical narratives. The tension between science and religion, and within systems of belief are central to both projects. In the work on technology, the concern that I have been exploring for almost ten years now, if not more, is whether AI can supplant our history and our science as a source of some kind of institution of truth. Each project explores how we know what we know, how it informs our social and political structures, and how epistemology develops – a kind of techno-episteme.

Continue reading “Magic, Religion, Science, Technology”

In considering technological theology, it is necessary to distinguish between what I refer to as transcendent theologies: belief, absolutes, or truth, and what I call lived theologies: scripture, ritual, mantra, holy places and order. Transcendent theologies are claims to higher knowledge, beyond what is possible in nature, in areas like life after death, and the existence of God (upper case ‘G’). Lived theologies are claims about how one should live in order to serve god (lower case ‘g’), what it means to live a good or successful life. Transcendent theologies in one sense do not matter to our life on earth; they are by definition unprovable, revealed to us through prophesy, and while they may inform our lived theology, they relate to a higher order of existence than that with which we are currently concerned. Lived theologies are extremely important, and while often informed by revealed religion, they predate all of the great modern religions. Each of us adheres to a lived theology, with some base understanding of right, and righteousness, whether that’s an altruistic, socially sensitive collectivism, or a Darwinist individualism. In each case we seek to advance our interests based on an understanding of the world, an evolved ontology – that is our lived theology.

Continue reading “Computational Theocracy”

In considering my proposal of technological theology as a waypoint in our current trajectory, from religious, political and economic theology, the idea of epistemic theology was brought to my attention in considering the grounding of Carl Schmitt. There have been questions about the theology of Schmitt (was he primarily Christian, or secular?), and some questions over whether political theology is about the politics of theology or the theology of politics; medieval political theology certainly appears to have been about the latter. Adam Kotsko suggests political theology is more concerned with the relationship between the two fields of theology and politics, though the consensus is moving towards what he calls a politically-engaged theology. My reading, reflects a range of kinds of theology, in that political theology is an ontological structure, allowing the world to be understood and engaged with. Just as Deleuze and Guattari argued that the role of the philosopher is to ‘create concepts’ (What is Philosophy?, 1991(FR), 1994(transl.), Columbia, p.5), so political theology is a way to understand the world, to understand the real in social, or more specifically political terms. It is, in Schmitt’s explanation, a secular theology (Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty, Chicago UP, 1985/2005).

Continue reading “Epistemic Theology and Epistemic Technology”

In his 1995 encyclical Evangelium Vitae (The Gospel of Life), the late Pope John Paul II defended capital punishment, ‘…to redress the disorder caused by the offence’. While the pontiff considered the problem ‘in the context of a system of penal justice ever more in line with human dignity,’ it was heavily caveated; it was an almost reluctant accession to conservatism. Nevertheless, ‘[p]ublic authority must redress the violation of personal and social rights by imposing on the offender an adequate punishment for the crime,’ the pope wrote. Within two years, however, it was no longer church teaching. The update in 1997 to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, while recognising that the death penalty had long been considered appropriate on the part of legitimate authority, that was no longer the case. ‘Today,’ the Catechism goes at section 2267, ‘there is an increasing awareness that the dignity of the person is not lost even after the commission of very serious crimes. In addition, a new understanding has emerged of the significance of penal sanctions imposed by the state. Lastly, more effective systems of detention have been developed, which ensure the due protection of citizens but, at the same time, do not definitively deprive the guilty of the possibility of redemption.’ In 2020, Pope Francis cemented the position of the Church in the encyclical Fratelli Tutti. ‘There can be no stepping back from this position. Today we state clearly that “the death penalty is inadmissible” and the Church is firmly committed to calling for its abolition worldwide,’ Pope Francis writes in section 263. How could an institution so committed to dogma, doctrine, and a unitary truth shift so dramatically in such a short period of time?

Continue reading “Temporal Gospel”The British Museum is a controversial edifice. In part a persistently triumphal display of looted treasure – such as the Parthenon Marbles and the Benin Bronzes – by a brutal and supremacist empire, part conservator of important artefacts of social history, its symbolism at a time of Brexit and resurgent nationalism is unhelpful to liberal sensibilities. It remains something of a contradiction that its erstwhile director, Neil MacGregor, combines a defence of its virtue as a world museum with criticism of the British view of its history in general as ‘dangerous’ (Allen, 2016).

Continue reading “Technologies of Theology”

AI poses several challenges for the religions of the world, from theological interpretations of intelligence, to ‘natural’ order, and moral authority. Southern Baptists released a set of principles last week, after an extended period of research, which appear generally sensible – AI is a gift, it reflects our own morality, must be designed carefully, and so forth. Privacy is important; work is too (we shouldn’t become idlers); and (predictably) robot sex is verboten. Surprisingly perhaps, lethal force in war is ok, so long as it is subject to review, and human agents are responsible for what the machines do: who those agents specifically are is a more thorny issue that’s side-stepped.

Continue reading “World Religions and AI”

What has happened to Europe? What of our glorious post-war project to bring together our cultured peoples after centuries of war, that brave experiment not merely in statecraft, but in post-state statecraft, to redefine government, and seize peace to our hearts? It has persevered and grown for over sixty years, launching exuberantly into the new Millennium with the Euro, but now she finds herself beset on all sides by vast forces including geopolitics, security, technology and global finance. Worst of all, Europe seems to have lost its soul. Not merely its raison d’etre, but its spirit, its ambition. What is missing?

Continue reading “The Lost Soul of Europe”

In his 1966 work The Order of Things, Michel Foucault describes in his preface a passage from Borges to establish his objective. Quoting Borges, who in turn refers to ‘a certain Chinese encyclopaedia’, the section describes a classification of animals as being ‘divided into: (a) belonging to the Emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies’. In a later lecture recalled by Laurie Taylor, Foucault lambasted the impulse to capture and mount every butterfly in a genus and lay them out on a table, to highlight minute differences in form and colour, as if trying to solve God’s puzzle. Continue reading “Reflections on Blackwater: Technological Theologies, Autistic Robots, and Chivalric Order”

(…continued from Alien Technology)

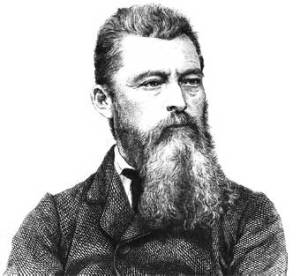

Marx’ extension of Feuerbach was accompanied by one of his more famous quotations. Writing in the Theses on Feuerbach, ‘the philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways,’ Marx said. ‘[T]he point is to change it.’ Feuerbach concerned himself with the spiritual and theological, while Marx was more revolutionary. How then could one take an abstract concept of alienation and explain how it meant something tangible, more actionable?