There has long been a persistent tension, a binary opposition in my thinking, between romanticism and enlightenment, faith and reason, spirituality and science. It was first awoken in my in depth research into the essence of technology, as it revealed itself as little more than an interaction with nature; and as my research into the philosophy of mind, agency, and time suggested, it was not all that clear that such interactions were intentional. All of that appeared to coalesce in Spinoza’s monism, his idea that there is only one substance, that each of us – and everything else that exists: rocks, trees, stars, time, even god – is part of a single thing, a single substance. Habermas claimed the ascendancy of the existential fissure in the Axial Age – the time of classical Athens, around 500BCE give or take. Neitzsche agreed, blaming Socrates, and looking instead to the pre-socratics for wisdom. Carlo Rovelli, whose The Order of Time I’m just about finished (such a lovely book – more on that later), goes to Anaximander (610 -546 BCE, roughly) to understand his modern science (in particular quantum mechanics) and its real meaning. However, most people today would identify the French Revolution and the late eighteenth century as being the true breaking point, when the Divine Right of Kings was abandoned, and Science asserted itself as our true…well, our true faith.

Continue reading “Resurgent, or Synthetic Romanticism”Category: Romanticism

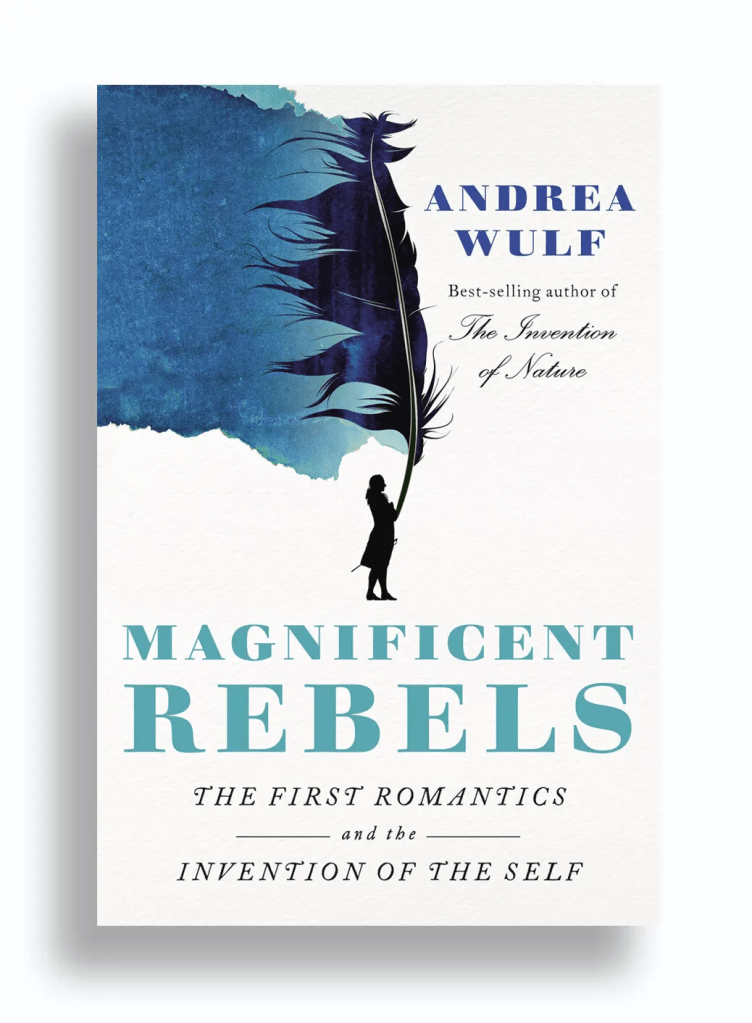

When we think of the romantics, at least in the Anglo-Saxon tradition, we often consider careful lovers in lace and ruffles, lovers primarily of love itself, as a noble, worthy aesthetic. We think of the poetry of Wordsworth (‘I wandered lonely as a cloud…’), Shelley (‘O wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn’s being’) and Coleridge (‘In Xanadu did Kubla Khan / A Stately pleasure-dome decree…’), or of Edmund Burke’s concepts of the sublime and the beautiful. Situated in late eighteenth century Europe, however, and juxtaposed with Continental romanticism, the picture becomes altogether more political, theological, and – though fractured into myriad interpretations – more substantial. It becomes, in essence, a reaction to the Enlightenment, to the new scientism, a rejection of dogma.

Continue reading “Hirschman and The Romantic Spirit”