I apologize for not having posted in 2025, but as I had mentioned in late 2024 I was writing a book. The book has been completed, the first one at least, and is off to see if any agent considers it worth hawking around. More on that as we get it. The second book has more to do with science, and how we understand the world, and prompted me to think about a kind of layering of thought, a progression of a sorts, that I have been through myself. It begins – as did this blog – with concerns for politics, and how we manage ourselves – political philosophies. AS one dives deeper into political philosophy, one is drawn into the history of political philosophy, and then the philosophy of history follows soon after. Epistemic concerns lead to the philosophy of science, and how we know what we know, before ultimately we end up back at the philosophy of mind, cogito ergo sum and all that.

Continue reading “Ontological Layering”Tag: Technology

In considering my proposal of technological theology as a waypoint in our current trajectory, from religious, political and economic theology, the idea of epistemic theology was brought to my attention in considering the grounding of Carl Schmitt. There have been questions about the theology of Schmitt (was he primarily Christian, or secular?), and some questions over whether political theology is about the politics of theology or the theology of politics; medieval political theology certainly appears to have been about the latter. Adam Kotsko suggests political theology is more concerned with the relationship between the two fields of theology and politics, though the consensus is moving towards what he calls a politically-engaged theology. My reading, reflects a range of kinds of theology, in that political theology is an ontological structure, allowing the world to be understood and engaged with. Just as Deleuze and Guattari argued that the role of the philosopher is to ‘create concepts’ (What is Philosophy?, 1991(FR), 1994(transl.), Columbia, p.5), so political theology is a way to understand the world, to understand the real in social, or more specifically political terms. It is, in Schmitt’s explanation, a secular theology (Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty, Chicago UP, 1985/2005).

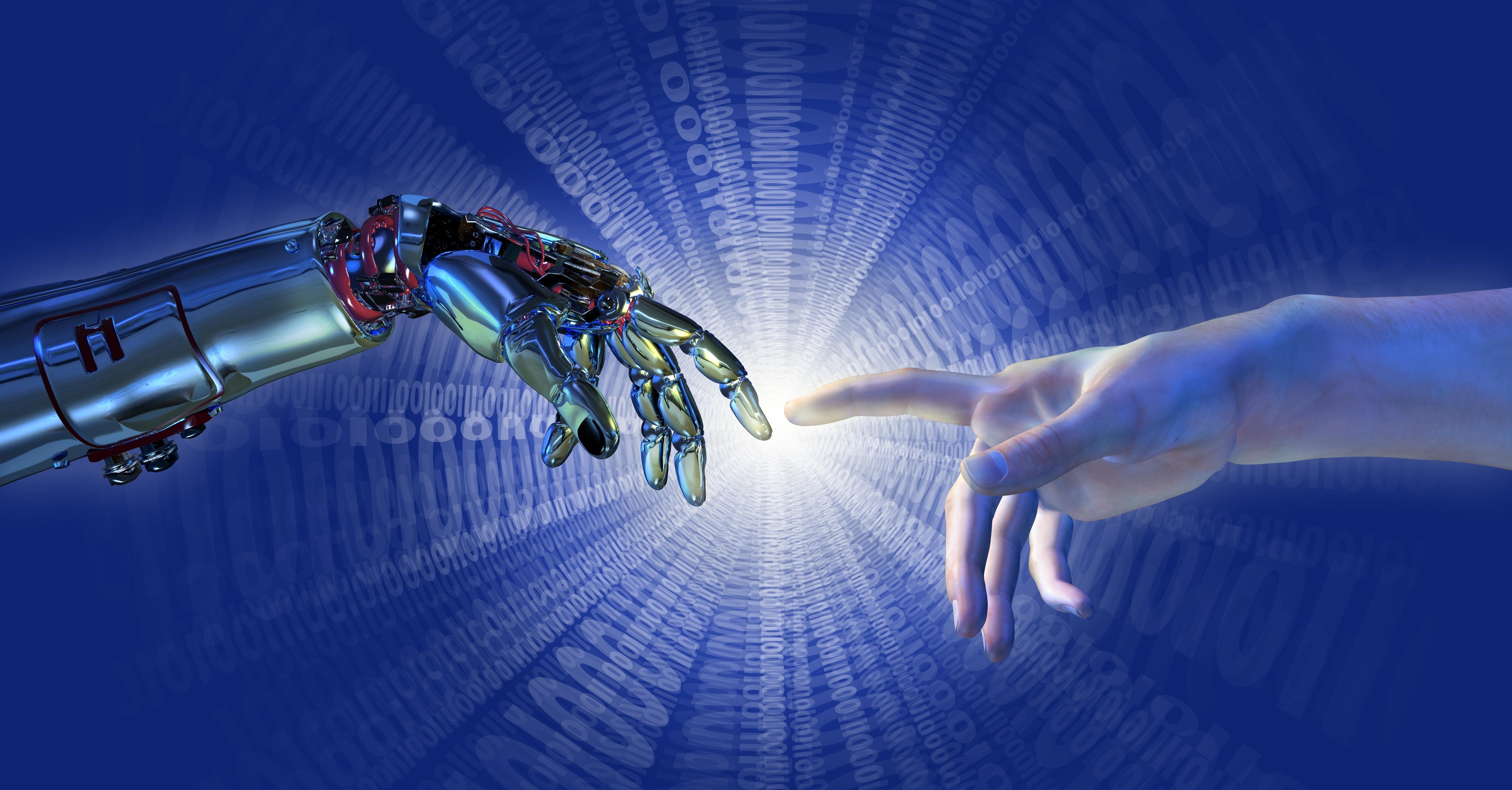

Continue reading “Epistemic Theology and Epistemic Technology”Twitter, Facebook and Google this week finally landed in exactly the position they have been resisting for ten years: front-row politics. In deciding to ban Donald Trump from their platforms, they have made a decision to decisively intervene in the US Presidency, denying one side its voice and making a judgement on the legitimacy or righteousness of that position. It’s really important to take a breath now, and understand just what this moment means.

Continue reading “Technopolitics”

In Giles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s 1991 book What is Philosophy?, the writers make the argument that philosophers are things of their time, creators of concepts through which the world can be interpreted. Philosophy, juxtaposed alongside science and art, provides the fundamental constructs that those disciplines require as a kind of prima terra, before any art can be made, or any science can be done. Philosophers, then, are in the business of creating ontologies.

This is of course a rejection of truth, at least in the absolute sense of the word. Richard Rorty distinguished between the concepts that ‘the truth is out there’ versus ‘the world is out there’. This goes all the way back to Wittgenstein and language, and the relations between the subject and the world: truth can only exist with language; and language can only exist with a subject. Therefore truth can’t exist ‘out there’, only the world can be out there – with its phenomenona (Husserl) and forms (Plato) and things-in-themselves (Kant).

Continue reading “The Ontologies of Technology”The British Museum is a controversial edifice. In part a persistently triumphal display of looted treasure – such as the Parthenon Marbles and the Benin Bronzes – by a brutal and supremacist empire, part conservator of important artefacts of social history, its symbolism at a time of Brexit and resurgent nationalism is unhelpful to liberal sensibilities. It remains something of a contradiction that its erstwhile director, Neil MacGregor, combines a defence of its virtue as a world museum with criticism of the British view of its history in general as ‘dangerous’ (Allen, 2016).

Continue reading “Technologies of Theology”

In Martin Heidegger‘s Being and Time, he refers to verfallen as a characteristic of being, or dasein. It means fallen-ness, or falling prey, an acknowledgement that we do things not because we want to do them, but because we must; we act in particular ways, we fall into line, we do jobs, have families, get a mortgage and a pension, obey the law and so on. We consciously engage with the systems and societies into which we have found ourselves. It is surprising how frequently this concept of ‘the fall’ emerges in philosophy, theology and popular culture.

Continue reading “Falling Down”

AI poses several challenges for the religions of the world, from theological interpretations of intelligence, to ‘natural’ order, and moral authority. Southern Baptists released a set of principles last week, after an extended period of research, which appear generally sensible – AI is a gift, it reflects our own morality, must be designed carefully, and so forth. Privacy is important; work is too (we shouldn’t become idlers); and (predictably) robot sex is verboten. Surprisingly perhaps, lethal force in war is ok, so long as it is subject to review, and human agents are responsible for what the machines do: who those agents specifically are is a more thorny issue that’s side-stepped.

Continue reading “World Religions and AI”

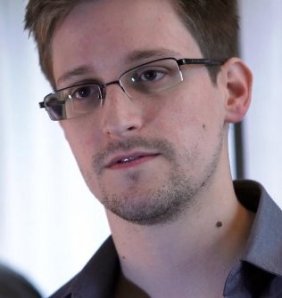

The New York Times and the Guardian have been digging ever deeper into the activities of the US National Security Agency or NSA following the leaking by Edward Snowdon of information about how they were spying both on countries and ordinary people at home. Hot on the heels of the Chelsea Manning and Wikileaks diplomatic cables episode, there has been a constant flow of stories reporting on nefarious activities of spooks and governments, embarrassing opinions, and the mechanisms by which international diplomacy and spying are conducted, though Wired Magazine had got there first. There are numerous angles to all of this. There is the technology problem, an Orwellian, Kurtzweilian post-humanist dystopia where technology trumps all, and big data and analytics undermines or redefines the essence of who we are and forces a kind of a re-evaluation of existence. There is the human rights problem, the balancing of the right to privacy and – generally speaking – an avoidance of judgement of the individual by the state, with the obligation to secure the state. This issue is complex – if for example we have an ability to know, to predict, to foretell that people are going to do bad things, but we choose not to do that because it would require predicting also which people were going to do not-bad things, and therefore invade their privacy, is that wrong? Many people said after 9/11 ‘why didn’t we see this coming?’ Which leads to the question – if you could know all that was coming, would you want to know?

Continue reading “National Security and the Legitimacy of the State”